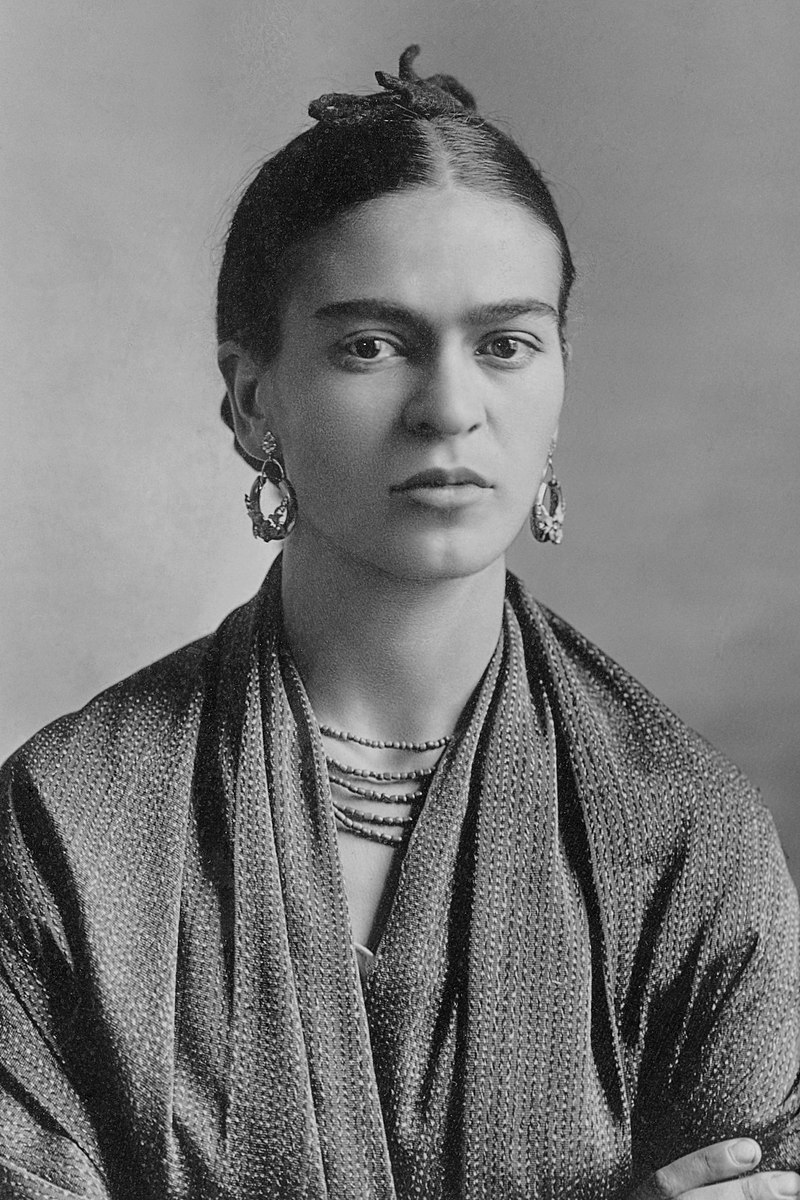

Why are we obsessed with Frida Kahlo?

Over the past several decades her popularity has soared. She is one of the most famous female artists in the world, instantly recognizable due to her thrilling self-portraits. Her fame has eclipsed that of her husband, mural painter Diego Rivera, who at the time they were married was the most important Mexican artist and a world celebrity. If Frida saw the intensity with which we scrutinize her artwork and examine her life today, she might be entertained by our behavior or even scoff derisively.

I will attempt to examine my own feelings in this short essay.

[This is not a biography. For a basic online bio click here. If you have access to PBS, I recommend the three-part series called Becoming Frida Kahlo. The film Frida is brilliant, and for an online gallery, click here. Books are many, but I started with Hayden Herrera’s, “Frida Kahlo: The Paintings” which is a modern day classic.]

Some might call Frida’s middle-class childhood sheltered, and her parents definitely indulged her. Her creativity was encouraged, and her wilder behavior was humored if not welcomed. Her father Guillermo was a photographer, and she spent many hours in his studio tinting pictures with him. She had a natural interest in drawing and went to college to study medicine. Then a bus accident changed her life forever at the age of 18.

Trapped in bed with devastating physical injuries and unable to return to school, Frida’s mind yearned for activity, so she began to paint. Bored with still life’s, her father rigged a mirror in her canopy bed so she would have an ever-present subject – herself. From this moment on, Frida’s self-portraits became her trademark.

During her lifetime, the subject matter of her paintings would include news events, politics, personal tragedies, family portraits, surrealistic interpretations of everyday life, flora and fauna of her native Mexico, and of course her compelling and sometimes shocking self-portraits.

Even by today’s standards, Frida’s subject matter can be disturbing. Our modern-day senses are numb to images of horrors seen every day when we turn on the television. Yet, when confronted by the intimacy of Frida’s “Henry Ford Hospital” that details the tragedy of her miscarriage, we are confronted by her pain and cannot look away. The dark humor of “A Few Small Nips” is gruesome, yet its true meaning lies in the pain Frida was feeling by the betrayal of her husband.

I discovered Frida in the 1980’s when I was given Hayden Herrera’s book as a birthday present. I had never heard of her before, and as I thumbed through the pages I was astonished. Who was this artist? The paintings were fascinating – and when did she paint them? In the 1930’s and 40’s? It was tantalizing to think that a woman who lived half a century ago had the gumption to make such bold artistic statements. During a time when Mexican women were still considered second-class citizens and would not have the vote until 1953, Frida said and did what exactly what she wanted. She painted her pain and anger, her visions and longing, her joy and her love – on the canvas for all to see.

Like a lot of people, I felt an emotional link to Frida when I looked at her paintings. It’s as if she were saying, “This is what I see in the mirror, and you are the only one I am telling”. She is able to make an intimate connection to her viewer.

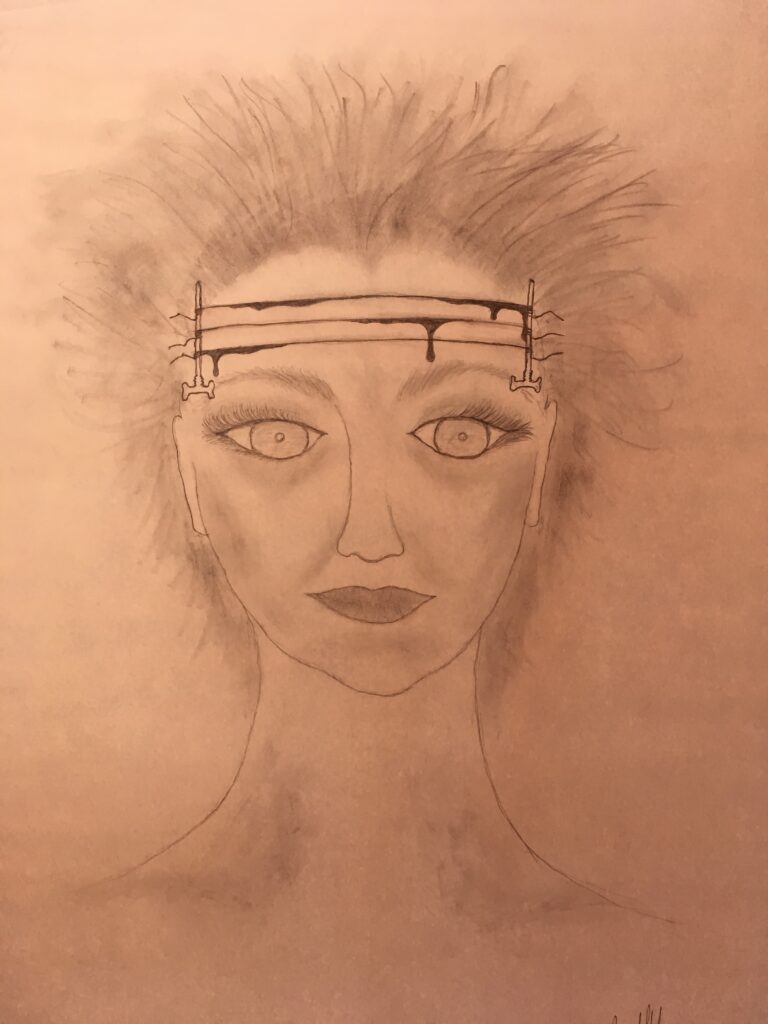

So, what did this mean to me? It felt important. As if Frida might be daring me somehow, with those dark eyes from under her exaggerated unibrow, to take a chance of my own. Could I illustrate my own pain, my own challenges? The concept was intimidating because I didn’t have the same level of artistic skills. Could I even be as honest as Frida? Could I look myself in the eye, even if I didn’t have the guts to show anybody else? I attempted to try.

Frida’s legacy gives us permission to be ugly. Permission as artists to show our own pain, to question society, and not care what anyone else thinks. She might be proud of how far we’ve come today, or she might be disgusted at the inequities we still endure as women, and the horrors the world still suffers.

I am reminded of her bravery every time I see one of her paintings, and aspire to always be honest – if not on canvas, at least with myself.

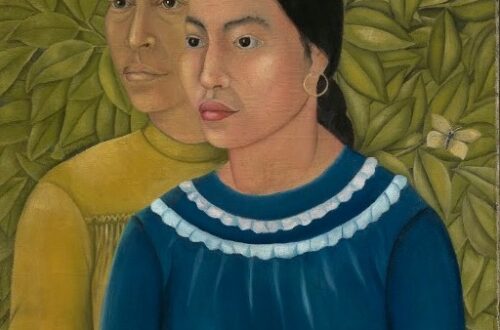

[When I studied at the Montserrat School of Art, I took an Art History class with the great Teresa Hunter-Hicks. When challenged by an assignment that required us to write about a painting in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, I chose to write about Frida’s “Dos Mujeres“, which had recently been acquired. Read it here.]