I grew up hearing stories about my ancestor, Captain Samuel Brockelbank, from my father and mother. In my small town of Georgetown, Massachusetts, he was famous. His former home, one of the oldest houses in town and now entitled “The Brocklebank Museum”, bore a sign during the 1970’s that read, “CAPTAIN SAMUEL BROCKLEBANK, KILLED BY INDIANS IN KING PHILIPS WAR”. To me a child, this seemed like a sad thing to announce on the outside of the home where the man once lived. It wasn’t until many years later that I understood the intricacies of early Colonial history in the Georgetown area, what King Philips War really was, and how my ancestor fit in.

“THE GREAT MIGRATION” – A Wave of 17th Century Immigrants

In our enlightened modern times, religious freedom is something we take for granted. We can worship (or not) in whatever style we choose. This was not the case in England during the early 1600’s. Stories of how Pilgrims came to the New World to seek religious freedom are familiar, but their travel plans were often motivated by life-or-death situations.

The direct cause of the immigration from England was King Charles I, whose controversial policies allowed the regime to manipulate and terrorize his subjects. He spent money foolishly, and his high Anglican form of worship and marriage to a Catholic bride made his subjects nervous. He spent time and money engaging France and Spain in frivolous naval conflicts. Charles was impulsive and dismissed Parliament three times between 1625 and 1629 (the American equivalent of firing Congress), vowing to rule alone – which was something that no monarch had ever done before. Many thought him insane, but under British law no one could safely challenge the King without risking their lives.

In addition, Charles organized the persecution of religious leaders who did not conform to the Church of England. His bishops sought to control what every minister and church leader said to his congregation. It was religious persecution not seen in England since the reign of Mary I (a/k/a “Bloody Mary”, a Catholic monarch notorious for “cleansing” the English population of Protestants by putting them to death). This blind oppression by those in power drove the migration of Puritans to New England to – quite literally – save their very lives.

Starting in 1629, entire Puritan families and parts of small boroughs began boarding ships for North America. In this manner, small sections of English towns simply moved over the Atlantic Ocean. Once Charles I restored Parliament in 1640, the parade of ships from England all but stopped, but not until 20,000 English citizens had abandoned their country for hopes of a better life in the new world.

Puritans and their descendants called this 11-year period “The Great Migration.” Those citizens who stayed in England and endured Charles’ oppressive policies called it “The 11-Year Tyranny”. Charles’ behavior almost ripped apart England and sent tens of thousands of former residents across the globe in an effort to escape, as they settled in new lands.

(Charles was executed for high treason in 1649, the only British monarch to suffer this particular political fate.)

FINDING A PLACE IN THE NEW WORLD – The Founding of Rowley

The John of London was a passenger ship that ferried travelers over the Atlantic during the Great Migration. In the summer of 1638, the Widow Jane Brocklebank and her two young sons Samuel and John boarded the boat with some of their friends and neighbors and set sail out of Yorkshire.

The name of the boat and date of arrival are well known because the boat also carried a piece of precious cargo: It brought the first printing press to the New World, a fact that was greatly anticipated and documented by local papers when the ship docked in Salem that December.

The English passengers onboard the ship were led by the Reverend Ezekial Rogers, who had worked as a rector in Rowley, Yorkshire. After spending the winter in Salem, the group headed north and settled a large tract of land – thus a new Town of Rowley in Essex County, Massachusetts was founded in 1639.

In 1639, Rowley was over 70 square miles of rich farmland and freshwater creeks that fed the Merrimack River. Over a period of about 200 years it gradually split off into different townships. In Colonial times this happened naturally when farmers negotiated over a creek or a fertile pasture, needing water and grazing rights for their cattle. Property lines changed frequently. Large towns such as Rowley with hard to navigate roads eventually developed two or three centers, each one with its own parish. With no paved roads it was difficult for farmers to bring their families long distances to Sunday services, so smaller boroughs were formed over time.

Today the Town of Rowley is around 20 square miles, while its original 1639 boundaries also contain Groveland, Georgetown and Boxford and also parts of Haverhill and Middleton.

SAMUEL BROCKLEBANK – An Involved Citizen

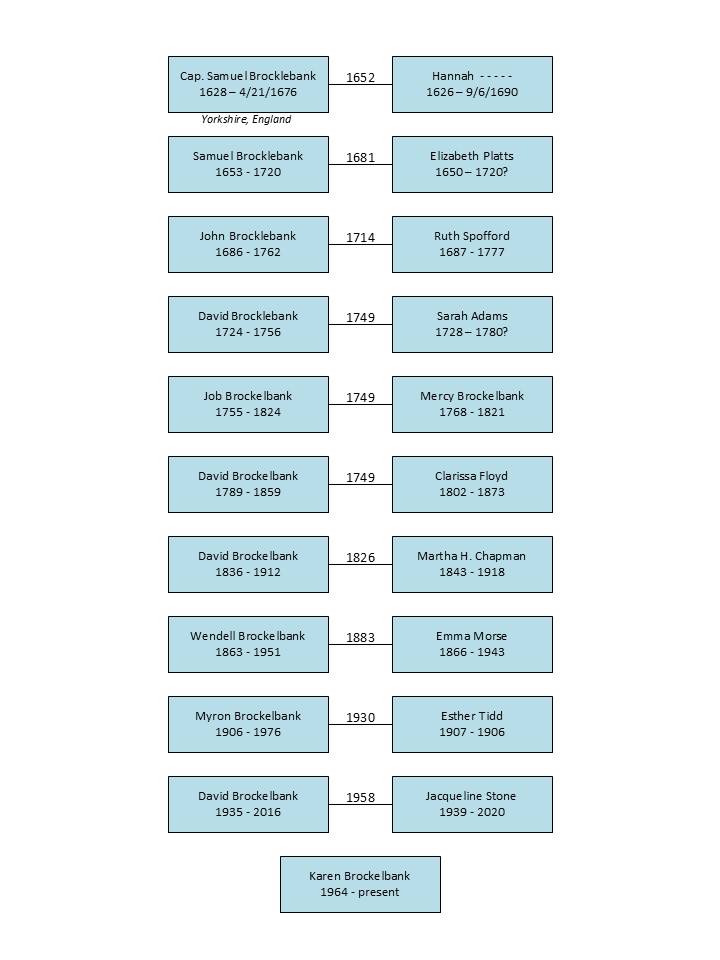

In 1652, Samuel Brocklebank married a local woman named Hannah. They made their home in what was then known as “West Rowley” – an area that would eventually become Georgetown. The house Samuel built across from the West Rowley parish spent several generations in his family, was added onto by different owners, and would someday become The Brocklebank Museum.

He and Hannah had a farm and kept livestock near Penn Brook, a freshwater source that feeds into the Parker River system and eventually the Merrimack River. Like other farmers, he probably developed a number of skills such as making shoes and tanning leather – and traded with his neighbors to sustain his family through the seasons. Samuel also filled important offices in town, including selectman and deacon. He was a good, upstanding citizen who supported his town and contributed actively to his community.

Since Hannah and Samuel had many children to support there was a lot at stake – especially since a domestic conflict was looming on the horizon. Years of mistrust and misunderstandings between Native American Wampanoag and Plymouth Colony leaders would eventually lead to King Philip’s War (1675-1678) – the only time in history when Native American tribes united to fight against English Colonists.

KING PHILIPS WAR – 1675 – 1678

After the death in 1660 of legendary Wampanoag leader Massasoit (who had helped the Mayflower passengers survive their first winter and maintained peace with English settlers) his two young sons Wamsutta and Metacomet took English names in order to move more freely between English and Wampanoag societies. Wamsutta became Alexander, and Metacomet became Philip. They even purchased English clothing and hired interpreters.

Only two years later, while negotiating with the Narragansett tribe, older brother Alexander and his troops were inexplicably detained by the English while south of Boston. After a short confinement, he was released; however, he fell ill and died before reaching his home. Due to a lack of communication and assumptions of hostility, it seemed to the Wampanoag that the English settlers had killed Alexander. The Wampanoag became enraged. Alexander’s younger brother, Philip, at the age of 24, was now in charge of one of the largest tribes of New England.

From the time Philip became Sachem in 1662 and the start of the war over a decade later there was an uneasiness between the English and Native Americans that rapidly escalated. Philip was trapped in the middle of a great territorial squeeze between England and France, with the English pushing from the east, and the western border of France’s Beaver Wars becoming ever closer. In January of 1675, Philip fired his interpreter John Sassomon, who was then found dead several days later under suspicious circumstances. When three Wampanoag natives were found guilty and hanged for the murder, Philip had finally had enough and declared war on the English settlers in June of 1675.

Historically, the Wampanoag had squabbled and fought with their neighboring Algonquin-speaking kinsman, but this time they had a common enemy. Alliances quickly sprang up with the Narraganset, Pequot, Mohegan, Nauset, Nipmuk, Massachusetts and several other tribes as they began to attack the English. Even the Mohawks, an Iroquois tribe in eastern New York, eventually joined the fight.

The first year of the war was the worst, as King Philip’s united army kept the colonists busy. They attacked and burned houses – sometimes entire towns – down to the ground. Colonists built fortified garrisons for protection and reinforced their ability to protect themselves by acquiring weapons, and making sure every able man took part in target practice. Local militia captains organized groups of armed settlers in an attempt to fight back. Unprepared for attacks of such force, many colonists, sheltering themselves in garrisoned houses, could do little but watch as their towns were destroyed.

Eventually the odds caught up with King Philip in August of 1676 when he was shot and killed. However, the war was far from over, as skirmishes kept up for several years. In the end, King Philip’s War war lasted four years from start to finish, devastating the population on both sides and breaking forever any trust that had been built up by Massasoit.

THE SUDBURY BATTLE – A Deadly Encounter

Samuel, like other able-bodied men, had volunteered to lead troops to protect those in his area. On April 21, 1676, in Sudbury, he and Captain Samuel Wadsworth of Milton led a troop of 60 men into the area – not knowing they were exceedingly outnumbered by over 500 members of various native tribes. The Sudbury fight was a brilliant victory for the native alliance as they obliterated the colonial squad. Wadsworth and Brocklebank, along with about 27 of their men, were buried in a mass grave. The Sudbury Fight would be one of the most famous battles of King Philips War.

A memorial obelisk in the Sudbury cemetery marks their final resting place. The Sudbury Historical Society, aware of the sensitive nature of Native American interests, hopes someday to memorialize the indigenous people who also lost their lives.

[100 years later, Philip’s ghost was raised at the beginning of another conflict, when British Redcoats would be termed “distant savages” that were just as easy to defeat… by Colonial-era politicians trying to motivate crowds to fight in what would become the Revolutionary War.]

“Distant Savages”

CONCLUSION – Finding Connections

I spent many years volunteering at my local historical society. Tracing your genealogy is a popular and satisfying pastime, made easy by many online services. As a tour guide at The Brocklebank Museum and a 9th great grandchild of Captain Samuel Brocklebank, I met many people from faraway places who traveled to Massachusetts to visit the museum. It was exciting to see their happy faces and hear them say “I traced my family tree! We’re cousins!” and watch them spread out their papers on our table and explain how they figured out all the puzzle pieces. As I listened to their stories and looked at their pictures, I knew that their visit to the museum was another cherished part of their family tree journey.

As a native Brockelbank descendent, living in the same town and connected to names on gravestones in all the local cemeteries, I joked with visitors that my still being local nearly 400 years later was due to a familial lack of motivation. However, the time I spent with these lovely people tracing their roots made me appreciate my own family tree even more, and made me want to learn more about the more distant branches I knew nothing about. It truly is a never ending journey.

I think it’s really something special to make connections to people, whether we are related through DNA or some other reason entirely. My years spent at the museum were very special, and my conclusion is that we are all cousins. All of us, humans, on the planet, are all connected. Our similarities are more important than our differences. We form a web that we shouldn’t take for granted.

Karen Brockelbank

Note: In the late 1700’s, some American Colonists began changing the spelling of their names to differentiate themselves from being citizens of the King. Thus, BROCKLEBANK became BROCKELBANK.